Postpartum Psychosis & Mother of Rain

Note from Jessica: I’m honored to have a guest post from Karen Spears Zacharias today about postpartum psychosis and her book Mother of Rain

Note from Jessica: I’m honored to have a guest post from Karen Spears Zacharias today about postpartum psychosis and her book Mother of Rain. This is an important topic that deserves attention and hope you will read on.

It was Christmas Day. I will never forget that. I’d called my best friend to wish her a Merry Christmas. She responded with a frightened whisper:

“I know what the problem is,” she said.

“Problem?” I asked.

“Yes,” she replied. “I know why I can’t get anything to eat. I can’t get into the kitchen.”

“Why can’t you get into the kitchen, honey?”

“Because the boys are at the table putting together a model airplane. I want them to do things like that but I can’t get into the kitchen to eat.”

Ten years had lapsed since my friend was institutionalized following the birth of her first-born. Here she was in the third-trimester of her second pregnancy and talking out of her head again.

“Honey, why don’t you just walk around the boys?” I suggested.

She paused for a long moment. “I’m not thinking clearly, am I?”

“No, you’re not.”

“Whatever happens, don’t let me hurt my babies.”

Don’t let me hurt my babies. Those were the words that reverberated in my newsroom cubicle a couple of years later when the AP wire reported that a Texas mother named Andrea Yates had drowned her five children in a bathtub.

Don’t let me hurt my babies came to me again when I heard Miriam Carey had been gunned down in D.C. after she tried to drive her car through barriers at the Capitol building. It wasn’t until after the unarmed woman was shot dead that police discovered a toddler in the car.

Postpartum psychosis is the official name for the illness, although we didn’t know that when the Yates children were murdered, or when my girlfriend attempted suicide six weeks after her daughter was born. Postpartum psychosis, an extremely rare, but too-often deadly, form of mental illness affects thousands of women every year. An average of 1.3 million pregnant women experience some manifestation of postpartum depression (PPD) annually, reports Katherine Stone, founder and editor of Postpartum Progress (postpartumprogress.com).

Miriam Carey was under a doctor’s care. Andrea Yates’s physician warned Yates after her third pregnancy to not get pregnant again. My girlfriend’s illness went misdiagnosed until that last attempt on her life, when her family realized what she needed wasn’t solely a psychiatrist but an endocrinologist.

The symptoms of postpartum psychosis are often excused as something all new moms experience: Irritability, lack of sleep, hyperactivity, mood swings, difficulty communicating.

What new mother hasn’t experienced one or more of these?

But the mother suffering from postpartum psychosis will also experience delusions, which she will rarely mention, because her delusions often involve doing harm to her children or herself. And because the paranoia invoked by postpartum psychosis prevents her from trusting others.

My girlfriend was convinced that the CIA was listening to her every thought. She saw roaches climbing the walls of her baby’s room. She thought her husband might be trying to harm her. Mixed into all that was overwhelming despair. My girlfriend felt that she was a bad mother because good Christian mothers don’t have the kind of thoughts she was having.

Had a doctor on vacation not discovered my friend lying on that beach that afternoon, an empty bottle of pills at her side, I would be writing about suicide, not postpartum psychosis. My girlfriend knows she could easily be serving time in a state hospital for the murder of her own children. She could have been gunned down by police in some awful confrontation gone awry.

Tell them what happened to me, my girlfriend said. Make others aware. Educate them so that what happened to me, what happened to Andrea Yates, what happened to Miriam Carey doesn’t happen to them.

Okay, I promised. But the problem with talking about a mental illness associated with motherhood is the stigma we attach to those who suffer from it. My girlfriend lives in the same community where she grew up, just blocks from the high school where she was a cheerleader, a homecoming queen, voted one of the top most-liked personalities among a class of hundreds. Everyone knows her, loves her.

It’s difficult for her, even decades later, to not feel like she let people down because of a medical condition so rare and so misunderstood that its name is never spoken from the pulpits or uttered in university hallways. How does a mother tell her children of the mental breakdowns their births invoked without terrorizing them, without leaving them feeling guilty or fearful that they, too, might suffer some silent disorder of the mind?

“What I wish most is that for one day of my life I could have known my mother the way you knew my mother – before her illness,” her son said to me upon his high school graduation.

Her children have never known a time when their mother was not under a doctor’s care. And although postpartum psychosis can be treated effectively, there is no getting around the fact that for a woman who experiences it there is a forever sense of lingering fragility. People look at you differently when you’ve suffered from mental illness. Even when you’ve healed, there remains the nagging “what ifs” in the minds of others.

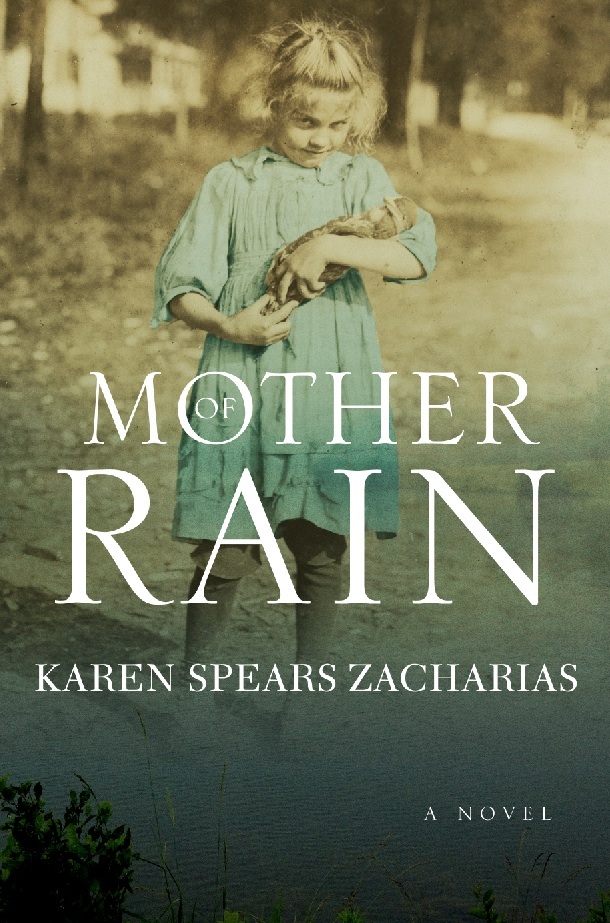

It’s that stigma that kept me from writing a non-fiction account of my girlfriend’s struggles. Instead, I turned to fiction. “Mother of Rain” is the story of Maizee Hurd, a young mother of a deaf child named Rain. On the heels of Pearl Harbor, Maizee’s husband Zebulon enlists in the Army and leaves Maizee and Rain to the care of the community of Christian Bend, Tennessee, a community I am quite familiar with. My aunt Lucille Christian lived there during my own growing up years.

I set the book in 1940s Appalachia because the isolation of that mountain community serves as a metaphor for the loneliness that women who suffer from postpartum psychosis endure. It also serves as a reminder that when it comes to mental illnesses and the health of women, progress is woefully lacking.

“Mother of Rain” is not my girlfriend’s story. It is not the story of Andrea Yates or of Miriam Carey. It is, however, informed by women who have suffered from postpartum psychosis.

What made the difference between my friend and Andrea Yates was simply the community that surrounded them. My girlfriend comes from a big Italian family. She is married to a man wholly-devoted to her. When she was ill, they refused to leave her alone for even one minute. They moved mountains to get her the medical help she so desperately needed.

Had it not been for the loving community who relentlessly nurtured her back to health, my girlfriend’s name – listed in the dedication to “Mother of Rain”- could have been as common among the general public as that of Andrea Yates.

Karen Spears Zacharias is author of Mother of Rain (Mercer University Press). She can be reached via Twitter @karenzach or at via her website @ karenzach.com For more information about postpartum psychosis check out postpartumprogress.com

Beautiful. Heart-wrenching. Thank you for sharing Jessica and Karen. I fully agree with your plight to bring awareness to this cause. I will definitely be purchasing this book. My thoughts & prayers are with your friend and any one else that struggles with mental illness from one degree or another. I myself have been battling it for years. It is a lonely, quiet, journey when it doesn’t have to be. I know I’m not alone but I also know that not very many people want to talk about it. Thank you.

Thank you so much for this! For loving your friend enough to really see her. This could be my story as well and I stand here today completely whole and well. But your words still take my breath away with their truth. Thank you for speaking truth for the whole world to hear.

Yes thank you for sharing your wisdom and awareness on this issue. I too suffered from severe post partum depression. I don’t even want to know where we would be had I tn gotten help when I did. This is needed. Awareness and openness is needed. Thank you for doing just that.